We asked the poets to write a sonnet

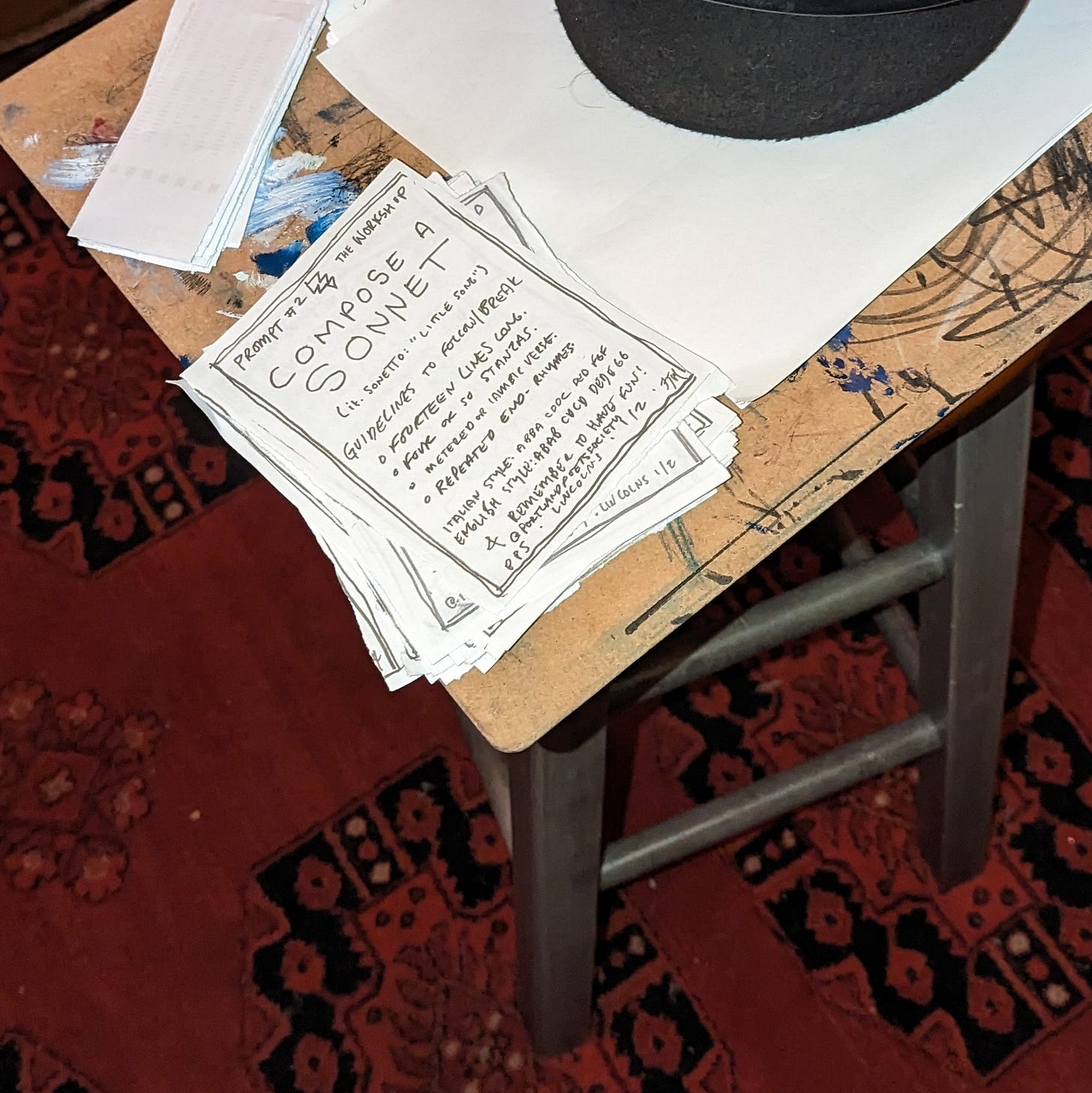

In my forthcoming Nightmares & Morning Pages post of January, you’ll read that we proposed sonnets to the Workshop - a smaller group and everyone writing, what a fever! I had a chance to talk w/ everyone who showed up, those I knew intimately, those I knew nothing about, and those I am still learning about. We handed out little slips of paper that went over - generally - what a sonnet has been in the past, encouraging all sorts of sonnets to come forward. And now we all have something to scrapbook.

Benjamine offered one of the more difficult e.e.cummings poems: Sonnet Entitled How To Run the World. (whew!) I do not read that one in the recording, sorry.

✺

I N T H E R E C O R D I N G

I brought in a piece by poignant poet oddball W.S. Merwin

A light summary from that linked article:

For the entirety of his writing career, he explored a sense of wonder and celebrated the power of language, while serving as a staunch anti-war activist and advocate for the environment. He won nearly every award available to an American poet, and he was named U.S. poet laureate twice. A practicing Buddhist as well as a proponent of deep ecology, Merwin lived since the late 1970s on an old pineapple plantation in Hawaii which he has painstakingly restored to its original rainforest state. Poet Edward Hirsch wrote that Merwin “is one of the greatest poets of our age. He is a rare spiritual presence in American life and letters (the Thoreau of our era).”

I found this sonnet and found it beautiful, indicative of that kind of ‘graceful urgency’ they mentioned in the article above. Similar to the T.S.Eliot piece that Savannah shared Burnt Norton and honestly every poet mentioned here (most poets probably), it muses on time and the everlasting flash in the pan that life is. The last line breaks my heart a little.

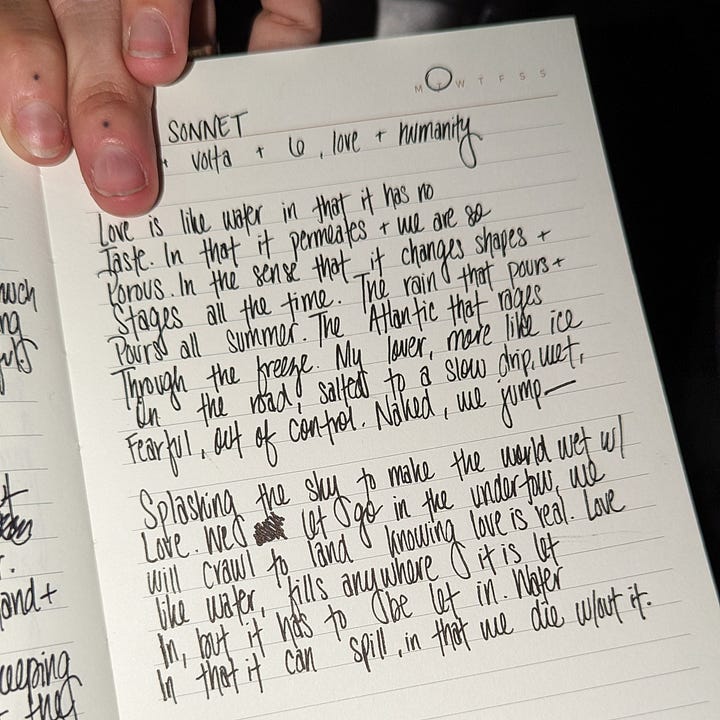

What I ended up writing was a more modern version of the sonnet and an easier way to approach it for me. I thought of romance, of satire, of humanity - turns out I have been thinking for a long time of romance, of satire, of humanity. I kept the Volta in mind from the beginning. I counted fourteen lines, about 10 syllables each line. With the time I had the week or so leading up, I didn’t want to contend w/ a rhyme scheme if I could write about something I was interested in exploring. Rather I pulled a couple lines I had written in my morning pages the day before and I let myself languish in what the poem was getting at.

W/ all my work, I spend a lot of time dancing around, zooming out, zooming in. The sonnet really gives you space to move w/ fourteen lines, most of them simply setting us up before the volta spirals in like gravity. In more modern poetry, we try and sum up what we’re saying quickly, directly, using our voices as arrows. As we go back to where poetry grew, it was long laments and rambling verses to obscure and trick and play, to romance and sing and mourn slow and deep; as slow as the feelings moved that was the speed of poetry. Now, we have less time to work, less tolerance for decoration. I worry poetry has been becoming too short, too tight and too clear. Returning to old forms not only can kick a habit but it can remind us why we write at all.

Many poets, I was delightfully surprised, chose to keep w/ some kind of rhyme scheme. But in talking w/ a few folks who felt as unattached to rhyming as I did, I offered they stick to the structure and move through it thematically. Where Benjamine and I stand, we are two sides of the joker card, top and bottom - his historic, floral roots that lend to absurdity and rhyme scheme and my roots on fire, floating up into the sky, seeing what sticks and trying to fly. There’s no right or wrong here, freedom is at its finest in poetry.

✺ In the spirit of the Internet, if anyone would like to participate virtually in the Workshop to some degree, please get in touch w/ me somehow and we can develop that together.